It’s been a very long time since I’ve reread anything that wasn’t a short story or a children’s book, but after an intense R.A. Lafferty binge about a decade ago, I thought it was time to return to some favorites and see how they hold up. And for whatever reason, I decided to skip right past a reasonably accessible title (Okla Hannali) and my personal favorite from last time around (Fourth Mansions) for the weird, epistolary The Three Armageddons of Enniscorthy Sweeny.

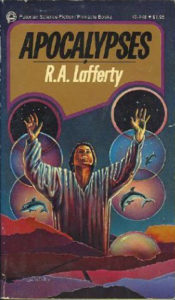

While not one of the novels that has been brought back into print, The Three Armageddons of Enniscorthy Sweeny is one of the easiest Lafferty titles to find at secondhand stores, bound together with Where Have You Been, Sandaliotis? (unrelated, except by author and themes of forgery and collective memory) in the two-novel collection Apocalypses. It is also a very hard book to describe. Even having read it once before, I had forgotten everything but the main premise: an idyllic twentieth century with no World Wars or Great Depression, interrupted only when a growing segment of the populace begins to believe that Enniscorthy Sweeny’s Armageddon Operas were reality.

My second read showed pretty clearly why I remembered merely the premise and little of the plot: there is little plot to remember, in a traditional sense. Rather than a straightforward narrative, the book consists of eleven chapters of various Sweeny-related ephemera. The first is chock full of tall tales of his life and has the feel of the first pieces of a documentary, before the second skips to an analysis of mathematics research that identifies Sweeny as the man who could destroy the world and sets a group of assassin mathematicians after him. The last nine include selections from Sweeny’s letters, reviews of his operas, reports from private investigators, an alt-history timeline of major world events, and more.

It is not an easy read, and two chapters in, I was wondering why I had liked it so much the first time. There were certainly lines that had me chuckling—pretty much a given when reading Lafferty—but the treatise on fictional mathematics struggled to keep my attention. And yet, even with the faux academic articles and the mystifying interlude that finds Sweeny building worlds with angels or demons or something else entirely, I ended up loving it just as much—and perhaps more—on second read.

Why, exactly? For two reasons. First, even when the overall narrative is cast in shadow, Lafferty has a tendency to make the individual moments enough fun to produce a pretty good reading experience. For nearly a week, my camera roll became a collection of particularly amusing passages, from assassins who persist in their task even after shuffling off this mortal coil, to a farcical play that saw the audience leave for the bar by the end of the first act, to piece after piece of incisive social commentary.

It’s that thematic work that provides the second major reason I loved this book. It’s too weird to ever feel preachy, but it has plenty to say on collective memory and societal response to tragedy, and that commentary feels even more apropos in the social media-soaked world that has arisen some 45 years after the publication of Apocalypses. There’s a sort of slipstream approach to history that never comes right out and says whether the horrors of the twentieth century were real or fictions—and whether or not Sweeny, by sheer force of will, had determined just which timeline held true—but it includes so many reflections on group consciousness that hit hard in a world where different political factions work with an entirely separate set of basic facts.

Even more pointed are the passages that indirectly put our twentieth century on trial, accusing the world of simply not acting like it suffered great atrocities or like it had any real interest in preventing more. Lafferty has his own convictions, and he alludes briefly to abortion, euthanasia, and widespread availability of deadly weapons for private use as particular examples of a world without a will to live. But the case against a society that has entirely failed to learn from its disasters and just doesn’t much seem to care whether it survives or not is a damning one, whether or not the reader agrees on each individual bit of evidence. And it’s a case that’s aged well (or poorly, depending on your perspective):

“If the world were really on fire,” a philosopher reasons with us, “then people would try to put the fire out. But they don’t really pay much attention to it. They gawk at it a little bit, but then they walk away and forget all about it. This proves either that the people have very slight attention spans or that it isn’t a real fire that seems to be burning the world. None of it is real, perhaps, or it would be more noticed. That stench of burning flesh is a fair facsimile of the real thing though.

Yes, and that was one of the better philosophers.

And the thematic work hits all the harder in contrast with the ambiguity of the story itself, which never quite says whether Sweeny was the one who threw open the clanging gates of hell or whether he merely drew attention to the fact by trying to close them–if there is even a fact of the matter at all. It spends a lot of time pointing a mirror at the world and more than a bit on Sweeny battling his own demons, but always in a way that yields more questions than answers, with the strange and illogical becoming commonplace, and with no neat resolution to tie everything together. There’s enough narrative cohesion to organize many of the subplots into something reasonably concrete, but it’s a reflective and experimental novel that absolutely resists being pinned down on the main questions.

And all told, it’s a wonderful book. There are parts that are difficult to read, and it’s simply not meant for readers who want to sink their teeth into a traditional story. But at just under 200 pages in total, even the difficult passages don’t last too long, and they are more than made up for by the humor, prescience, and delightful weirdness that makes for the sort of book that feels like four stars during the read and is an easy five a week later—it only gets better upon reflection.

Recommended if you like: experimental New Wave sci-fi, weird epistolary slipstream alt-history.

Can I use it for Bingo? Also hard to pin down, but I suppose it’d be hard mode for Magical Realism/Literary SFF and Mundane Jobs, and I’m fairly certain there is an Angel or Demon. Being under 200 pages, it’s often called a Novella—I doubt it’s actually under 40,000 words, but I can’t confirm either way.

Overall rating: 18 of Tar Vol’s 20. Five stars on Goodreads.